In the previous issue, we discussed ways of bringing back food plants our ancestors used, but which have become neglected and underutilised in recent times.

By using these plants in the diet, African families will get the nutrients they need on a sustainable and affordable basis, and it will help fight health and developmental problems caused by malnutrition.

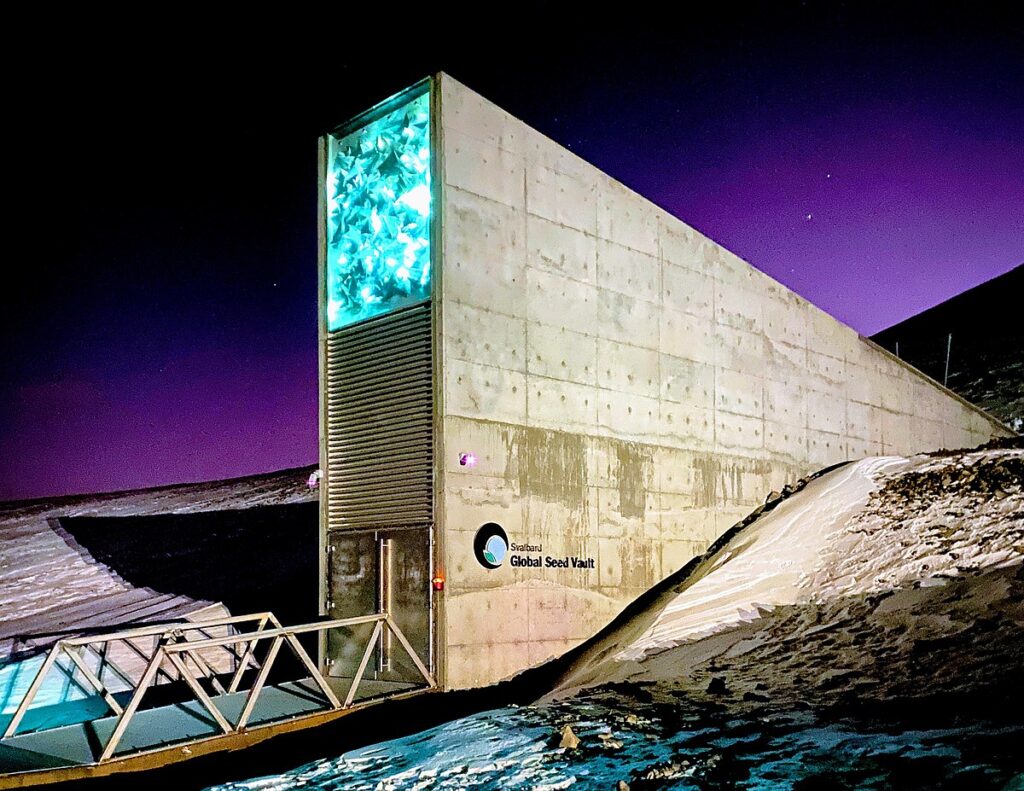

In this issue we look at global initiatives, such as the Global Seed Vault in Norway and the World Vegetable Centre (WorldVeg), and what they are doing to ensure that a variety of plants survive for biodiversity and food security.

The Global Seed Vault

“A seed is a time capsule,” says Jurie van der Walt, who has been studying and writing about ancient plants that have become neglected and underutilised species (NUS). “Seeds can be stored for hundreds of years, and even thousands of years.”

This Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, Norway, was built to store about 500 seeds each of 4,5 million varieties of crops. The Vault officially opened on 26 February 2008 and has since received more than a million distinct crop samples, representing more than 13 000 years of agricultural history.

The seeds were donated by almost all the countries in the world. The Vault does not store genetically modified seeds, as the Norwegian law prohibits it.

The Vault is a backup facility for the world’s crop diversity. It provides longterm storage of seeds duplicated in gene banks around the globe to protect the world’s food supply against the loss of seeds due to equipment failure, accidents, mismanagement, a cut in funds or natural disasters.

The Vault functions like a safe deposit box in a bank. The contents of the box remains the property of the person who deposited it, and only this person has access to the materials.

The seeds are sealed in three-ply foil packages before being placed in plastic containers that are stored on metal shelves.

The seeds are stored at −18 °C. Limited access to oxygen ensure low metabolic activity and delay the aging of the seeds. The permafrost surrounding the facility helps maintain the low temperature of the seeds in case of a power failure.

Indigenous vegetable seeds are being harvested in India.

The World Vegetable Centre (WorldVeg)

The International Year of Fruits and Vegetables was celebrated in 2021. The year also marked the fiftieth year of existence of the World Vegetable Centre. This international non-profit research institute was established to help smallholder farmers and local communities in developing countries to increase the production of vegetables.

WorldVeg was founded as the Asian Vegetable Research and Development Centre in 1971. The name changed to World Vegetable Centre in 2008.

For the first twenty years, research focused on the sweet potato, but now it is focused on three groups of globally important vegetables. These include solanaceous crops, which include tomato, sweet pepper, chili pepper and eggplant; bulb alliums, like onion, shallot and garlic, and cucurbits, including cucumbers and pumpkins. They also do research on the indigenous food plants of Africa and Asia.

These vegetables are researched so that WorldVeg can provide seeds of nutritious plants at an affordable price to farmers, who can also sell excess food for an income.

WorldVeg keeps the world’s largest public collection of vegetable seed, with about 70 000 accessions, or products derived from 440 vegetable varieties from 158 countries.

WorldVeg maintains vegetable biodiversity by conserving genetic material, called germplasm, mostly in the form of seeds of these plants that are either cultivated in gardens, or gathered from the wild.

Jurie explains: “I had the opportunity to talk to the Head of WorldVeg’s gene bank in Africa, Dr Sognigbe N’danikou, who joined Worldveg in April 2019 as scientist:

Traditional Vegetable Conservation and Utilisation

“Dr N’danikou’s task is to maintain and improve the traditional African vegetable germplasm collection and associated documentation at the WorldVeg gene bank in Arusha, capital of Tanzania. WorldVeg provides seeds for safekeeping in the Global Seed Vault.

“The Centre’s research and development work focuses on breeding improved vegetable lines, developing and promoting safe production practices, reducing postharvest losses, and improving the nutritional value of vegetables.”

Besides research, the centre also builds networks and do training and promotion to raise awareness of the role of vegetables for better nutritional health, and ultimately to alleviate poverty.

Dr N’danikou also explains that the centre stores seeds of the ancient and indigenous food plants of Africa and to make these available to farmers for multiplication. These food plants include African eggplant, African nightshade, Amaranth, Jute mallow, Spider plant, Okra, Moringa, Roselle, Cow peas, and Mung beans.

The Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, Norway, where seeds from all over the world are kept in case a calamity threatens food security and plant biodiversity.

Vegetables a pathway out of poverty towards better health

Dr Roland Schafeitner, a researcher who leads the vegetable diversity and genetic improvement programme at WorldVeg, believes almost a billion people around the world suffer chronic malnutrition, two billion have micronutrient deficiencies and another two billion are overweight.

According to Jurie, Dr Schafeitner also believes that improved vegetable production systems and new ways to process, market and trade produce, can provide income for smallholder farmers, especially women and youths. New ways to farm can also reduce the impact of farming on the environment, while making the soil more fertile so that crop health and yields can improve.

The doctor states: “You can earn more money with a hectare of vegetables than with a hectare of rice or wheat. Vegetables are a pathway out of poverty.”

According to Jurie, three billion people around the world are unable to afford a varied healthy diet. “There is a need to tackle the issues around the availability, accessibility and affordability of fruits and vegetables.”

The lack of healthy, nutritious fruit and vegetables leads to stunted growth in millions of children; many millions of women of reproductive age suffer from serious vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and a billion people, including children, adolescents, and adults, are overweight or obese.

“This represents a major burden on the social and economic development in low- and medium-income countries,” says Jurie. “Research studies indicate that the greatest food security challenge in 2050 will be providing nutritious diets rather than adequate calories.”

Low productivity

Although smallholder farmers in Africa grow indigenous, healthy, and nutritious foodplants as a pathway to healthy living as well as an income, low productivity remains an obstacle.

Low productivity, which ranges from 35% in sub-Saharan Africa, 47% in South-East Asia, and 64% in South Asia, leads to a short supply of nutrient-rich vegetables.

In these regions, among others, the low productivity, the unavailability of vegetables, and a poor vegetable value chain, are caused by technological and socio-economic factors. This is made worse by climate change, which causes higher temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, and the occurrence of extreme weather patterns.

According to Jurie, a recent study of global vegetable and legume production found that if greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions continue at the present rate, with the resulting higher temperatures, water scarcity and increased salt content of the soil, vegetable yields could drop by 35% by 2 100.

WorldVeg stores seeds of indigenous plants and provide samples of all to the Global Seed Vault.

Vegetables must be able to adapt

To change this course of events, it is important to ensure that the vegetables can adapt to environmental changes. Therefore, the research conducted by the WorldVeg Centre in Arusha has for the last fifty years focused on improving vegetable varieties and production systems to cope with high temperatures and weather extremes in tropical and sub-tropical regions.

The centre is therefore able to expand its research to make vegetables even more resilient to climate change, such as reducing inter-season variability (able to grow in all seasons) and prevent losses after the vegetables have been harvested.

Production and supply (push factors) need attention in Africa, where 13% of the countries provide enough vegetables, compared to Asia, where 61% of the countries do. Demand and activism (pull factors) must grow the consumer’s choice and preference for fruit and vegetables.

Jurie believes education on all levels is necessary to change people’s behaviour. They must learn about nutrition, the social norms of healthy eating, and must start taking charge of their diets and therefore their own health.

Contact Jurie van der Walt at jurievdw@mweb.co.za. His books are freely available on request. The history of food and why we eat it (2020), and We need to revive the ancient indigenous food crops of Africa (2021).

Svalbard Global Seed Vault (2021, December 12). Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Svalbard_Global_Seed_Vault

World Vegetable Centre (2021, November 21). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Vegetable_Center