The occurrence of wet, muddy conditions and accumulation of manure, do not only make the production of hygienic milk difficult, but also contribute to mastitis, hoof and leg problems, and reproduction and respiratory problems.

Muddy conditions

Although it stands to reason that a cow will soil her udder and teats while lying down in the mud, the spread of manure and mud to her udder resulting from her movements, may not be that obvious. Abe (1999) carried out a study to determine how impurities spread to a cow’s udder from her legs and tail as a result of her movement.

This study proves that a cow carries impurities by means of her natural leg movements to many areas of her udder when she steps in mud or deep manure. These include areas not usually noticed in dairy situations.

Good sanitation, or a docked tail, is two possible solutions for keeping a cow clean. Many people feel that the tail is necessary for controlling flies, but other alternatives exist, as the tail is a feeding source for flies. Improved housing, a docked tail or the clipping of the tail can be considered to prevent contamination of the udder.

Dirty legs contaminate the bedding with bacteria found in manure and mud. Although the growth of bacteria will depend on the bedding, it will grow and create a greater risk of mastitis infection.

Corrals, roads, grazing, shed entrances and walking surfaces, as well as bedding, must be kept clean and dry. High-flow areas such as fodder and water troughs must especially be kept spotless. If soil conditions are very poor, the areas must be fenced and, under very severe circumstances, the cows must be kept inside.

Dairy procedures must be adapted to muddy conditions. The udder must not be summarily washed with hot water. This will spread the mud to the teats. Many farmers waste money to keep udders clean and dry under unfavourable conditions. A better option is to rather address sanitary problems, as good sanitation leads to higher quality milk and fewer cases of mastitis.

Muddy conditions have a detrimental effect on a cow’s hooves. (Photo by geography.org.uk)

Accumulation of manure

An accumulation of manure in the manure alleys of intensive housing units can increase the concentration of ammonia (NH3) and carbon dioxide (CO2) in the air significantly. Ammonia gas is released from fresh manure and the further aerobic breakdown of manure and urine, while a large quantity of CO2 is produced daily by the breathing of animals and the breakdown (rotting) of manure. The resistance of animals against pathogens can be decreased by the inhaling of gases such as carbon dioxide, ammonia and methane. Fodder intake and, consequentially, production can also be influenced adversely. Daily cleaning of manure alleys and good ventilation is therefore essential.

Sainsbury, according to Engelbrecht (1991), alleges that the threshold values of ammonia gas and CO2 in the air of intensive housing units, are given as 50 and 500 parts per million respectively. It seems, though, that animals can endure considerably higher concentrations of these gases for short periods.

A docked tail.

Disease control

The prevention and control of diseases are of the utmost importance for success in a dairy enterprise. To prevent diseases in a dairy herd, the dairy cattle must be well fed and the herd, farmstead and grazing must be kept clean. Especially note the health of animals introduced into the herd. If the dairy herd is well fed, the cattle will have better resistance to diseases.

Although there are a great many diseases that can affect dairy cows, only the two most important ones are discussed, namely mastitis and hoof and foot injuries.

Accumulating manure produces gasses like CO2, methane and ammonia which are toxic and pose a severe threat when it gets out of hand. (Photo by Pixabay)

Mastitis

The word mastitis simply means ‘inflammation of the udder’ and is usually caused by infection of the udder by bacteria. Mastitis can be described as acute, sub-acute or chronic, depending on the intensity and duration. The exceptions are cases caused by environmental pathogens.

Mastitis. (Photo by Nadis.org.uk)

Clinical mastitis

Clinical mastitis is easily detectable in the abnormal appearance in the stripping jug. It will also be visible in the reddish colour, heat and swelling of the udder, accompanied by pain.

Sub-clinical mastitis

Sub-clinical mastitis is easiest diagnosed in the laboratory. The udder looks normal but the somatic count is higher and bacteria are usually present. Mastitis is comparable with an iceberg. The clinical cases are the visual parts of the iceberg, while the sub-clinical cases are those parts of the iceberg which are underwater and invisible.

Somatic cells

Somatic cells are white blood cells, which are part of the body’s defence against bacteria and invasive microorganisms. These cells are always present in the bloodstream and in the milk, but their numbers increase visibly when infection is present.

A cow should have a somatic cell count of less than 100 000/ml. Older cows should have a somatic cell count of less than 250 000/ml, but it can be as high as 500 000/ml. Normal physiological deviations occur during the lactating period.

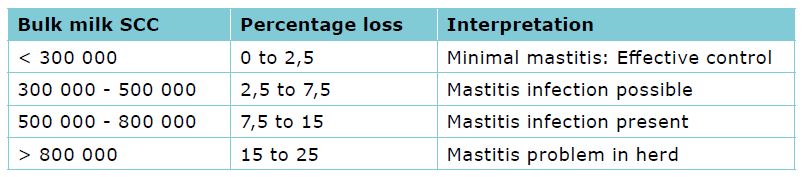

The somatic cell count (SCC) of bulk milk is a good indication of milk quality, milk loss and the effectiveness of mastitis control in the herd, as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Somatic cell count (SCC) of bulk milk as an indication of loss in milk production and the effectiveness of mastitis control in the herd.

Hoof and foot injuries

There are four main factors that can lead to lameness or that can react upon each other to cause clinical signs of lameness, namely:

- Hereditary factors (mass and composition)

- Feeding factors (proteins, vitamins, minerals and poisonous substances)

- Infection factors (bacteria and viruses)

- Environmental factors (climate and housing)

The foot and the hoof are the areas most affected by lameness problems, with 80% of the injuries taking place in this area. The remaining 20% of injuries associated with lameness is spread over the entire body and limbs. It is associated with the joints and ligaments and is mainly attributed to trauma.

Most lameness problems begin with hypertrophy (overgrowth) of the hoof. It usually occurs in cattle on high levels of concentrate fodder. Hypertrophy also causes the opening between the claws to cicatrise (grow together), with the result that the dirt is caught in them. This can lead to infection of the skin between the claws (foot-rot).

Decaying of the soft heel is also aggravated by hypertrophy, because a cow with extremely long hooves is inclined to walk on her heels. This increases decaying of this sensitive area. Softening of the hooves during lengthy wet conditions causes the hooves to have less resistance and are therefore made more susceptible to injuries and infection. In extremely wet conditions, or when animals are compelled to stand in wet muck, sole ulcers can develop. Under such conditions foot baths can relieve the condition.

Bovine Para botulism is a more complex problem and has its origins in feeding habits. Increased histamine levels in the blood cause the inflammation of the sensitive hoof tissue. High levels of concentrate feeding, silage rich in non-protein nitrogen or high levels of rumen-catabolic protein can lead to an excess production of ammonia in the rumen. The problem can be solved by correcting the imbalance in the total ration and by ensuring that sufficient fibre is available. The clinical injury of botulism is ulceration of the soles. These ulcers usually develop on the weight-carrying hoof and inflammation can easily set in. This can lead to serious, deep-rooted infection of the foot.

Hypertrophy of a cow’s hooves can lead to disease and lameness. (Photo by tbasine.wordpress.com)

Implementation of a health programme

Take care not to over-trim a cow’s hooves. (Photo by agritrimhoofcare.com)

The following general health programme can be implemented to prevent the occurrence of diseases and the spreading of infectious diseases and to control parasites:

- Gestating cows must get enough exercise, preferably by letting them graze on adequately fenced grazing where sufficient shade and water are available.

- Ensure that premises and corrals are well drained and kept as dry as possible to prevent breeding places for foot rot and parasites. For the same reason, fence off grazing where mud holes and puddles are present.

- Drainage from adjacent farms must preferably be diverted and communal fences that allow direct contact between cattle must be avoided. Do not visit farms where contagious diseases occur, as shoes, clothing and vehicles transmit the organisms. Fodder must not be purchased from such contaminated farms. Fodder bags must not be re-used.

- Rented grazing areas where cattle spend the winter must be avoided. Use grazing where no cattle grazed for a year or grazing that has been ploughed.

- Follow a healthy feeding programme to avoid ketosis, milk fever and nutritional diseases.

- Avoid injuries by keeping wire, nails and loose metal objects away from cows.

- Avoid heifers’ first time calving problems by feeding them generously and only breed when the heifer is large enough for a bull that breeds calves that are small at birth.

- Keep sick or infected animals away from others and obtain the services of a veterinarian.

- Early diagnosis is the key to quick treatment and recovery.

- Isolate all new additions from shows or auctions to the herd for a period of three weeks.

A cow’s hooves are her mode of transport. They should be kept in a running condition. (Photo by agritrimhoofcare.com)

Published with acknowledgement to the ARC Agricultural Engineering for the use of their manuals. Visit www.arc.agric.za for more information.